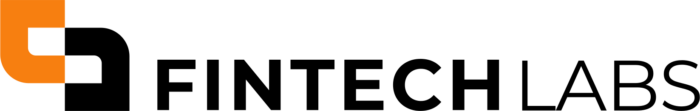

Bank of America’s email last week introducing its chatbot Erica made me wince (see above). And I wondered why. I crave self-service in all transactions, so I am pleased that banks are using AI/ML/DL, or most likely, just common sense, to solve my problems without talking to a human. But do I really want to converse with a robot, or do I just want to have my problems solved?

I’m comfortable talking to Siri or Alexa, but they sit in a different space than a bank’s voice interface. Alex needs to be awakened to do its job. But if you are already on BofA’s mobile app, there isn’t the same need to announce your arrival (see note 1). It’s a good UX improvement to give users the option to make a voice or chat query. But I don’t see the benefit of “naming” the voice response unit. It reminds of Microsoft Clippy, an automatic windows popup “helper” used from 1997 to 2001. I thought it was cute at the time, but people don’t want cute getting in the way of their task accomplishment, they want speed and accuracy. Anything that takes away from efficiency is potentially annoying.

I’m comfortable talking to Siri or Alexa, but they sit in a different space than a bank’s voice interface. Alex needs to be awakened to do its job. But if you are already on BofA’s mobile app, there isn’t the same need to announce your arrival (see note 1). It’s a good UX improvement to give users the option to make a voice or chat query. But I don’t see the benefit of “naming” the voice response unit. It reminds of Microsoft Clippy, an automatic windows popup “helper” used from 1997 to 2001. I thought it was cute at the time, but people don’t want cute getting in the way of their task accomplishment, they want speed and accuracy. Anything that takes away from efficiency is potentially annoying.

In such a new area, there isn’t a body of research to fall back on when making a decision. But I did find an interesting post from an exec at Intercom, a digital messaging company. Originally, they named their bot, but they found that is was intimidating to users. It wasn’t until they eliminated the name that users began to appreciate the self-service tools.

What we found was surprising. People hated this bot — found it off-putting and annoying. It was interrupting them, getting in the way of what they wanted (to talk to a real person), even though its interactions were very lightweight. We tried different things: alternate voices, so that the bot was sometimes friendly and sometimes reserved and functional. But we didn’t see much change. It was only when we removed the bot name, took away the first person pronoun, and the introduction, that things started to improve. The bot name, more than any other factor, caused friction.

Intercom concluded they needed to make the chatbot invisible so that it didn’t get in the way of the interaction.

Making technology disappear so that it becomes a true tool for humans— like a hammer, or a nail, or a pencil — that’s the true measure of success for today’s designers. And making tools quieter to use, so we can use them more intuitively— that’s the true measure of success for a designer who deals in words.

Moving forward:

You absolutely should be investing in making your banking app and customer service run without human interaction, whether by voice commands, typing or touch. Customers want to get in and out of their banking app as fast as possible, so the UX improvement and cost savings potential are significant. But put your money into an efficient UX, not a cutesy name (see note 2).

Notes:

Notes:

1. I’m not talking about Alexa skills here. “Alexa, what’s my Bank of America balance” is a great use of voice technology. But, saying “Alex, ask Erica what my bank balance” is redundant and a bit silly.

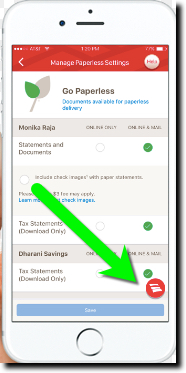

2. Other than the awkward introduction to Erica when you first start using it, BofA avoids using the name and simply posts a BofA logo in the lower right of each screen (see screenshot right). Pressing it opens up the chatbox interface where you can type or speak your question. That’s great customer service. But I bet they’d get better takeup if they stopped “introducing” you to a robot the first time.

BofA’s uses a “floating” logo in the lower-right

of each page to activate it’s Erica self-service tool.